Tchaikovsky

www.tchaikovsky-research.net

Tchaikovsky's interaction with dancers

Thanks for your excellent and thorough replies to my last question.

I've been enjoying Tchaikovsky's review articles on the site. He is a very engaging writer, and I frequently laugh out loud his descriptions of inadequate opera performances. Yet though he is often critical, he is never uncharitable. You never get the sense he wants to belittle a person as a person however great their artistic shortcomings might be.

I was wondering if we have any documents that shed light on Tchaikovsky's interaction with the dancers who performed in his ballets?

From what I've read his main dealings were with Petipa and choreographers. But I would love to know if he recorded any of his reactions to the dancers, either in performance or personally. I suspect their social standing was only on the edge of respectability, is this right?

Regards,

Tim Passmore

08/12/2012 02:21

An interesting account of Tchaikovsky’s acquaintance with the Russian ballerina Mariia Anderson (1870–1944) can be found in: David Brown, Tchaikovsky Remembered (1993), where an extract from her memoirs is cited (p. 81–82):

Pyotr Ilich Tchaikovsky had taken note of my performance, and at one of the rehearsals of some ballet in the winter of 1889 had asked our ballet master, Marius Petipa:

‘What’s the name of that young dancer who performed Cupid in the ballet The Vestal?’

‘Mariya Anderson,’ replied Petipa.

I vividly recall that conversation. It took place on the proscenium of the Maryinsky Theatre, close to the orchestra, five or six steps away from the first slips on the right-hand side. Pyotr Ilich was in a blue jacket; as always, his pince-nez hung on a black cord. During conversation Tchaikovsky had the habit of playing with his pince-nez with his right hand.

Petipa’s eyes were searching for somebody. Noticing me, with a wave of his hand and the words ‘ma belle’, he summoned me to him. I approached timidly and stood a little way off. They had not interrupted their conversation in French, and seemed not to be paying the slightest attention to my approach. From the separate phrases that reached me I understood that they were talking about the staging of a new ballet, The Sleeping Beauty, and in particular about me, although my name was not spoken. Imperceptibly, furtively, Pyotr Ilich stole a glance in my direction, evidently assessing me as a dancer. Judging by the expression on his slightly smiling face I satisfied him. Several of his exclamations, clearly and intelligibly repeated in French, confirmed my assumption. Finishing the conversation, Pyotr Ilich took several steps in my direction in his characteristic way – with a slight inclination of his body. Approaching more closely, he began asking me various questions, by habit mixing Russian and French, and playing with his pince-nez. When Pyotr Ilich had completed his questions, to which I had replied timidly and with reserve, Petipa, thinking I did not understand French, began explaining to me in his broken Russian-French dialect what they had been talking about. ‘Translated’, this signified that in the ballet The Sleeping Beauty I was to dance ‘the little cat – so Tchaikovsky wishes’.

The full text of Mariia Anderson’s recollections of Tchaikovsky is available in Russian on the excellent Tchaikov.ru

website [http://www.tchaikov.ru/memuar123.html

] and it is worth quoting further from them:

When staging the ballet Petipa gave careful consideration to that number [“Puss-in-Boots and the White Cat”] and worked on it for a long time. Which is not surprising. The music for it seems to imitate the mewing and hissing of cats. The dancing steps were put together in a very talented manner. Of course, all my efforts were concentrated on justifying the expectations of the great composer and the famous choreographer.

The ballet The Sleeping Beauty achieved a colossal success. It was first staged on 3/15 January 1890. The principal success undoubtedly fell to the lot of Tchaikovsky’s remarkable music. The dancers were in effect reduced to a supporting role. The audience’s attention was riveted to the music, the wondrous scenery and the lavish costumes. All this distracted the audience from the choreographic part of the ballet, and the dancers were jealous of the music.

It seemed to me that only I had any cause to rejoice since I had been given such an advantageous number in my duet with the dancer Bekefi. It was very much a masterpiece of musical onomatopoeia. In short, I was successful in this ballet; my efforts and diligent preparations had not been in vain. The staging of The Sleeping Beauty coincided with the first steps of my artistic career and that is why it has engraved itself in my memory extraordinarily vividly.

After The Sleeping Beauty Tchaikovsky wrote the opera The Queen of Spades, which was produced on 7 December 1890. I can still see Petr Il’ich before me as he talked to the singers who were performing the principal roles: Medeia Figner (Liza), Nikolai Figner (German), Mariia Slavina (the Countess), Leonid Iakovlev (Eletskii). The orchestra was conducted by Eduard Frantsevich Nápravník. The choreographer was Petipa. At the first three performances Matil’da Kshesinskaia and the author of these lines appeared in the pastoral intermezzo. The opera had a staggering, extraordinary success – almost impossible to describe. The newspapers and journals extolled the composer and his genius.

My next meeting with Petr Il’ich took place during the performance of the ballet The Nutcracker. After Act I, in which I had played a doll, all the dancers headed for the stage exit. I also rushed to my dressing-room in order to get ready for Act III, where I was to appear in the Chinese Dance: Tea. As I was making my way through the corridor that led from the stage I heard voices calling my name: “There she is, there she is! Mariia Anderson, hey...” I didn’t understand what they wanted, but some dancers and singers shoved me into the opera director’s room, which was packed full with people as always. Petr Il’ich was sitting on a divan on the right-hand side of this large room, surrounded by the first performers of Iolanta. The singers were looking at some photograph which they were passing round. When I walked in Petr Il’ich got up and cast a searching glance around the room. When he had located and retrieved the photograph he handed it over to me. At the same time he said something which I didn’t hear because the composer’s quiet voice was drowned by the awful din being made by those surrounding us.

In a flurry I timidly walked up to him and it was only when I heard his gentle voice and saw his friendly smile turned towards me and his grey eyes looking at me affectionately that I calmed down a little. Petr Il’ich asked me about the roles I was dancing and, in particular, about the role of the ‘little cat’. While talking he would address now me, now the singers, and only then did these at last fall silent. The people in the room formed a tight ring around us and listened to Petr Il’ich as he told them of how he had made my acquaintance, of the impression I had made on him when I danced Cupid, after which he had conceived the idea of entrusting me with the role of the ‘little cat’. ‘Ma belle’, ‘charmant’, ‘la petite Marie’, ‘je suis très content’ – these were the words with which he interspersed his account.

This praise, the joy and embarrassment that I felt, being the centre of everyone’s attention – all this caused me to lose my head yet again, and I pressed ever more tightly against my chest his precious present: the photograph of Peter Il’ich Tchaikovsky. With gesticulations I expressed as best as I could my joy and extraordinary gratitude for the honour which had befallen me. Opening my arms in a greeting gesture, blowing kisses as it were, elated, joyful, as if carried on wings, I rushed out and headed for my dressing-room. There the other girls, my fellow dancers, surrounded me, snatched the photograph from me and vied with one another to decipher the inscription which Petr Il’ich had made on it. It was only after I had calmed down a little that I managed to read what Tchaikovsky had written: “To the most delightful and talented ‘Little Cat’ and ‘Doll’ as a souvenir. P. Tchaikovsky. 1892”. I piously treasure the memory of that day as something quite exceptional, outstanding and unforgettable.

The premiere of the opera Iolanta and the ballet The Nutcracker took place on 6 December 1892. Within less than a year we were all staggered by the great composer’s death. Petr Il’ich loved everything that was beautiful... he loved Nature, flowers... he particularly loved lilies of the valley. How many of these flowers were placed on his coffin, which I too followed, together with an endless stream of mourners. I had placed my wreath next to the coffin. I was dazed with grief. It seemed to me that something infinitely dear and close to me had departed from my life.

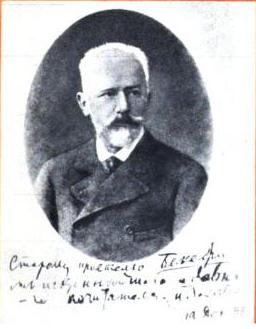

Although the photograph that Tchaikovsky inscribed for Mariia Anderson does not seem to have survived, a similar photograph that he inscribed for her fellow dancer, the Hungarian-born Al’fred Bekefi (1843–1925), who was the first performer of the Hungarian Dance at the premiere of Swan Lake in Moscow on 20 February/4 March 1877 and five years later danced Prince Siegfried in the same ballet, and who, as mentioned above, partnered Anderson as Puss-in-Boots in Act III of The Sleeping Beauty, was published in Ilya Zil’bershtein’s article “Triumf russkoi muzyki. Turgenev o Musorgskom i Chaikovskom” [The Triumph of Russian Music. Turgenev on Musorgskii and Tchaikovsky] in Ogonek in 1973. The inscription reads: “To my old friend Bekefi from his most sincere and long-standing admirer, P. Tchaikovsky. 12 December 1892”.

In the notes accompanying Mariia Anderson’s memoirs on the aforementioned website http://www.tchaikov.ru/memuar125.html

] the recollections of one of the pupils of the Imperial Theatre School who took part in the Christmas Tree scenes in Act I of The Nutcracker at the premiere are also cited. He recalled how during dinner after classes the following day the School’s inspector told the assembled pupils that Tchaikovsky had been very pleased with their performance and had sent some sweets for them. The two school porters then walked in carrying large baskets filled with boxes of sweets. Each pupil and instructor at the School received such a box.

That Russian dancers were already then held in considerable esteem by society is attested, for example, by the fact that the wedding of the Mariinskii Theatre’s prima ballerina Ekaterina Vazem (1848–1937) to the surgeon Ivan Nasilov (1842–1907) in January 1887 was attended not just by Petipa and other colleagues of Vazem’s from the ballet world, but also by Nasilov’s fellow professors at the Medico-Surgical Academy, including Borodin, who described the occasion in one of his last letters.

Luis Sundkvist

26/12/2012 16:20

The photograph which Tchaikovsky inscribed for Mariya Anderson has in fact survived and was published in the Photographs section of the second Almanac of the Tchaikovsky House-Museum: П. И. Чайковский. Забытое и новое [P. I. Tchaikovsky. Forgotten and New Material] (2003). As for the photograph for Alfred Bekefi, that was recently presented by Ronald de Vet in his article ‘Vier Photographien und ein Fächer’ [Four Photographs and a Fan] in the journal Mitteilungen of the Tschaikowsky-Gesellschaft (No. 18, 2011), where we find the following additional information (p. 4):

Apart from Modest Tchaikovsky’s The Life of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky [where the furore caused by Bekefi’s dancing of the Gopak at the first performance of Mazepa in the Mariinsky Theatre on 7/19 February 1884 is mentioned], Bekefi does not figure in any biography of the composer. Moreover, no letters from Tchaikovsky to Bekefi or vice versa are known [as confirmed by Dr Polina Vaidman of the Tchaikovsky House-Museum]. This photograph is probably the only documented testimony of the amicable relations between the composer and a dancer who was involved in the early successes of his stage works.

Luis Sundkvist

15/04/2013 23:45

http://forum.tchaikovsky-research.net

Please note that we are not responsible for the content of external web-sites