Tchaikovsky

www.tchaikovsky-research.net

"Figaro qua!"

A lost Tchaikovsky manuscript rediscovered in Stockholm

In August 2010, Marina Demina, a librarian at the Music and Theatre Library of Sweden (Musik- och teaterbiblioteket) in Stockholm, discovered an autograph manuscript by Tchaikovsky which had long been thought lost.

In this article, first published in Swedish

and in Russian

on her library's website in November 2010, and included here with her kind permission, the author explains how this discovery came about, as well as its significance.

|

|

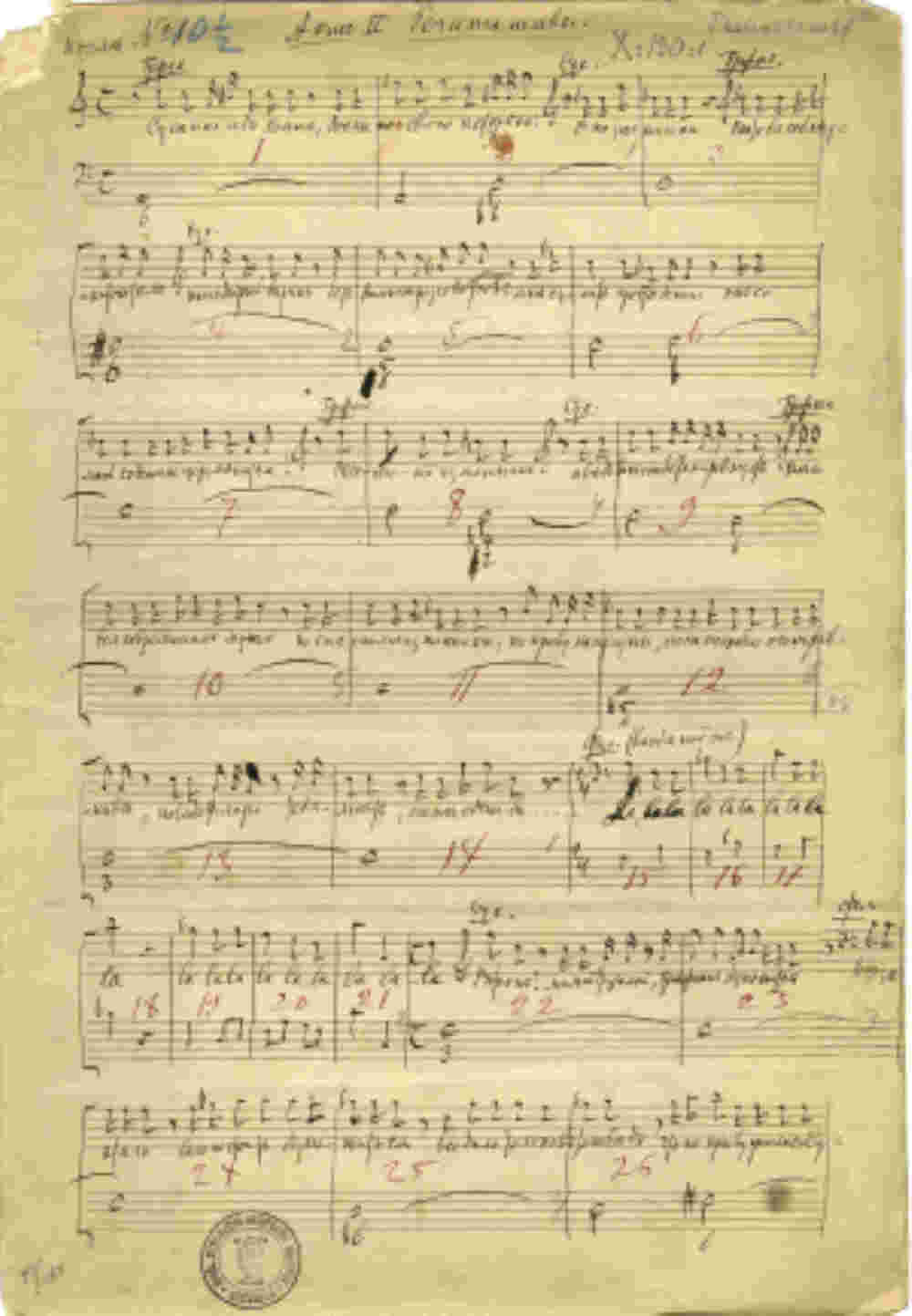

Picture courtesy of the Music and Theatre Library of Sweden |

A manuscript has been discovered at the Music and Theatre Library of Sweden in Stockholm which for more than a century was believed to have been lost. The document in question is an autograph manuscript by Tchaikovsky: his adaptation into Russian of the recitatives for Acts II to IV of Mozart's opera The Marriage of Figaro, as well as of the recitative coming after the eighth number in Act I: «Что значит эта комедия?...» ("Cos’è questa commedia?"). Tchaikovsky translated Da Ponte's libretto into Russian and edited the recitatives in 1875 at the request of Nikolay Rubinstein, who wanted to stage a student performance of Mozart's opera at the Moscow Conservatory. The autograph manuscript of all the Act I recitatives (dated 1875), except for the one mentioned above, is preserved in the Glinka National Museum Consortium of Musical Culture, Moscow [1] . Consequently, the fragments I have discovered can also be dated to 1875.

According to the reference number marked on the first page of the manuscript (—99/184) the latter was added to the archives of what was then the Library of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music in 1899. An entry in the accessions register for that year records that "Ett manuskript af Tschaikowski", as well as a small collection of printed music (including the scores of almost all of Tchaikovsky's symphonies), was donated to the library on 1 September 1899 by a certain Chrisander. The manuscript was placed in the autograph collection and given the file number X:130:1. The librarian dealing with this acquisition wrote the surname Tchaikovsky on both the catalogue card and the first page of the manuscript without any initials and also put a question mark next to the name. This was probably because Tchaikovsky had not signed the manuscript in any way, so that the only source of the attribution was the oral testimony of the donor, Chrisander. This document subsequently escaped the attention of researchers for more than 110 years, evidently due to geographical factors, i.e. the out-of-the-way location of Stockholm.

The manuscript consists of twelve sheets of 14-stave music paper (37.8 x 26.1 cm). Sheet 1 is double-sided and includes pp. 1-2, the reverse side having been left blank. Sheets 2-11 are enclosed with the first sheet and all have music and text written on both sides. Sheet 12 (the recitative from Act I) has writing on just one side. In total there are 23 written pages.

Mozart's famous opera of 1786 was very rarely included in the repertoire of Russian opera-houses during the nineteenth century. It was performed for the first time in Saint Petersburg in 1815 by a German opera company, and subsequently, after having been forbidden for several decades, by an Italian troupe in 1851. The Tsarist censorship, like that of the Austrian Empire, was not particularly happy with the anti-feudal message and subversive spirit underlying its plot.

Tchaikovsky, who worshipped Mozart, translated the libretto of The Marriage of Figaro in 1875. It was the first Russian translation and is in use even to this day. The piano-vocal score published by Jurgenson in Moscow in 1884 includes a foreword by Tchaikovsky, in which he discusses above all the problems involved in translating the dialogues (recitativo secco). According to Tchaikovsky—though the censorship was no doubt also looming in the background—he had taken the liberty of modifying various "unsuitable" expressions. In a letter to his publisher written at the same time Tchaikovsky puts it more bluntly, explaining that he had felt obliged to amend certain "salacious passages" [2].

On 5/17 May 1876 The Marriage of Figaro was performed at the Moscow Conservatory, with Nikolay Rubinstein conducting. The opera, however, was not premièred on the imperial stage—the Saint Petersburg Mariinsky Theatre—until 25 September/8 January 1901. Well into the twentieth century Mozart's opera was most often staged in Russia in Tchaikovsky's skilful translation. The piano-vocal score based on his version was reprinted several times, including in 1925 and 1956. The text was published as a separate booklet by Jurgenson in 1887.

The recitatives for The Marriage of Figaro in Tchaikovsky's Russian translation and as edited by him were published in the Soviet edition of his 'complete' works: Полное собрание сочинений, том 60 (1971). This publication was based on the incomplete autograph of Act I (from 1875), a complete manuscript copy (with the full accompaniment, but without the vocal parts; dated to 1884), and also the first edition of the piano-vocal score of the opera brought out by Jurgenson in 1884. The Tchaikovsky scholars and editors preparing these recitatives for publication in the New Edition of the Complete Works (Muzyka, Moscow, in collaboration with Schott, Mainz) will now be able to draw on the complete autograph of ČW 417.

Nils Chrisander (1846–1918), born in Stockholm, worked as a proof-reader at P. Jurgenson's music-publishing house in Moscow in the 1880s. His name is frequently mentioned in Tchaikovsky's correspondence with Jurgenson—amongst other things, in connection with the preparations, in 1884, for the edition of the first piano-vocal score of The Marriage of Figaro with Russian text, based on Tchaikovsky's earlier translation.

Letter from Jurgenson to Tchaikovsky, Moscow, 3/15 May 1884:

"Figaro is being published only for the sake of your translation, and that is why it is impossible not to pride oneself on the translator. […] However, the Swede Chrisander continues to insist that your recitatives here and there diverge from the Breitkopf edition. Shall I send you that edition?" [3]

Letter from Tchaikovsky to Jurgenson, Kamenka, 8/20 May 1884:

"Send me Figaro in the Breitkopf edition, dear fellow, so that I can clarify Chrisander's doubts" [4]

According to documents in the archive of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music in Stockholm, Nils Chrisander studied piano at the Academy's conservatory from 1861 to 1865. After moving to Russia around 1876 he would live and work there right until 1915. His principal occupation would probably have been giving piano lessons. Apart from Tchaikovsky's letters we can also pick up Chrisander's 'trail' in the biographical literature about the famous Russian pianist Josef Lhévinne (1874–1944): Chrisander was his first teacher, from the age of five until his enrolment in the Moscow Conservatory, where the young Lhévinne continued his studies (1881–86) in the piano class of Vasily Safonov.

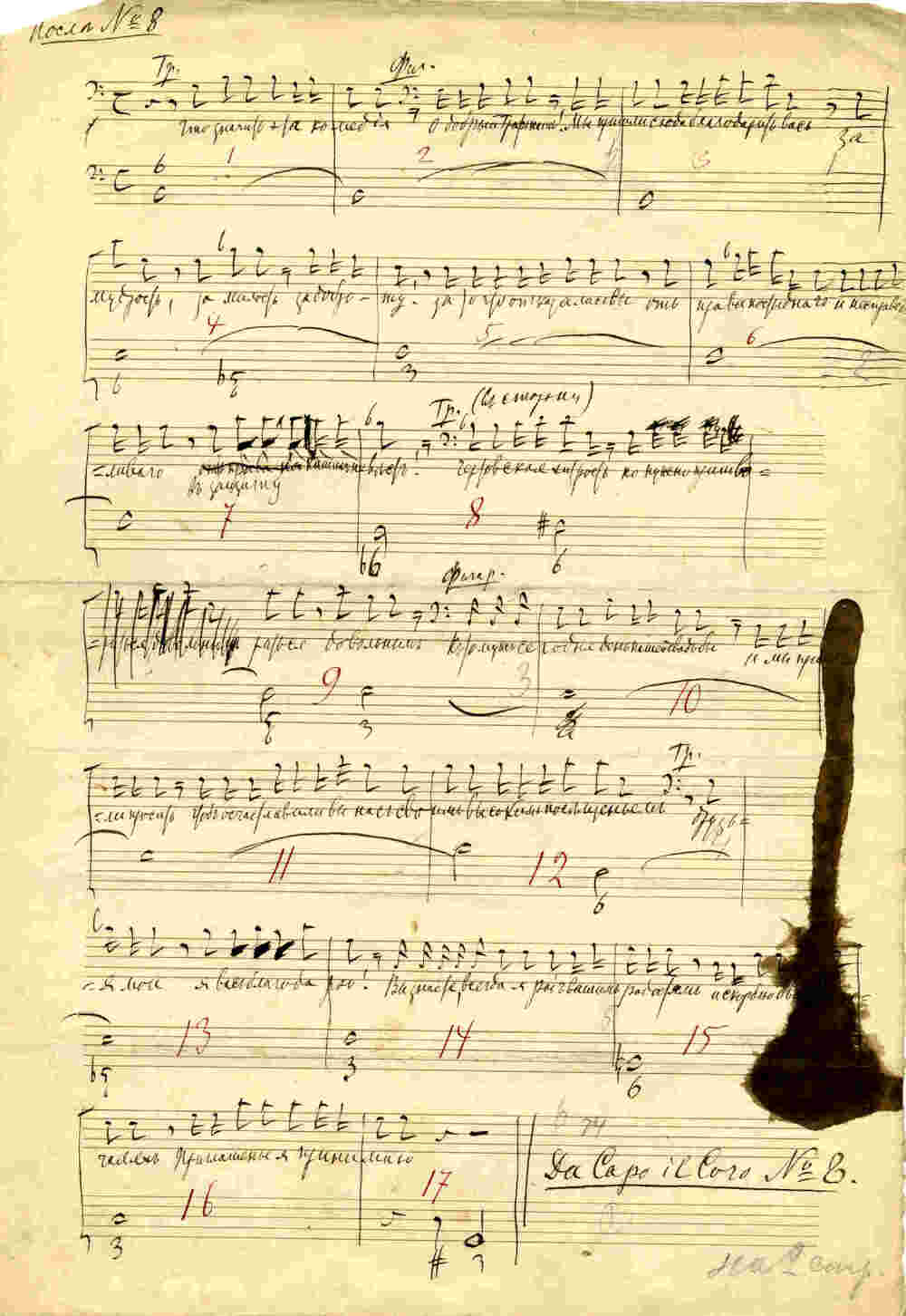

|

|

Picture courtesy of the Music and Theatre Library of Sweden |

Chrisander also composed a little himself, as well as compiling collections of simple piano pieces and exercises for beginners. These were quite popular and ran into several editions, even during Soviet times. Judging from his letters, Jurgenson thought rather highly of the "Swede" as a proof-reader, even to the extent of defending him when Tchaikovsky, at the start of the 1890s, increasingly expressed his discontent with the quality of the work done by Chrisander and several other employees of the publishing firm.

I have not yet been able to establish the year in which Chrisander stopped working for the Jurgenson firm, and one can therefore only speculate as to how such a large portion of the autograph manuscript of the recitatives for The Marriage of Figaro ended up in his possession. We know that Pyotr Jurgenson would often seek to retain the manuscripts of the works by Tchaikovsky that he published, and that he kept these in a safe on the premises of his firm. He repeatedly stressed that he was doing so with a view to preserving them for posterity and eventually making them over to some state archive. We also know that Tchaikovsky, when asked, would generously give away fragments of his musical manuscripts. Thus, for the time being it remains unclear whether "our" manuscript was a gift to Chrisander, or whether it simply ended up in his possession by chance. Likewise, it is unclear why the former proof-reader decided already in 1899—probably during a visit to his native country—to hand over the manuscript to the Library of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music. The most important thing, however, is that the manuscript has survived to the present day. A complete copy of it will now be sent to the Tchaikovsky House-Museum at Klin.

Marina Demina

The Music and Theatre Library of Sweden, Stockholm

English translation by Luis Sundkvist

References:

- See ČW 417 in the Thematic and Bibliographical Catalogue of P. I. Čajkovskij's Works (2006), and TH 187 in volume 1 of The Tchaikovsky Handbook (2002) [back]

- Letter 2498 to Pyotr Jurgenson, 31 May/12 June 1884 [back]

- Letter from Pyotr Jurgenson to Tchaikovsky, 3/15 May 1884 (quoted from П. И. Чайковский. Переписка с П. И. Юргенсоном, том 2 (1952), p. 9) — Klin House-Museum Archive [back]

- Letter 2485 to Pyotr Jurgenson, 8/20 May 1884 [back]

Article copyright © 2010 by Marina Demina

Photographs copyright © 2010 by Musik och teaterbiblioteket